Today, I have the honor of explaining to you the most popular thought experiment of our time. Fasten your seatbelts, we’re in for a ride.

- What is the Trolley Problem?

- Utilitarianism

- Kantianism

- Utilitarianism vs Kantianism

- Fat Guy off the Bridge Variation

- Bringing it all Together

Note: If you’re short on time and just need the fundamentals of the problem (main arguments, one variation, etc), go here to get it.

The Trolley Problem (Classic)

You’re a diligent, honest worker chopping away on the railway tracks in Victoria London. All of a sudden, you see a trolley barrelling down curiously fast. And ahead of the trolley…ahead of the trolley lies disaster!

The trolley’s current path, which it itself cannot deviate from (assume its “brakes” aren’t working), will lead it to kill four workers tied to the ground. You, however, see a lever that will change the trolley’s path to one that will lead to the killing of one worker tied to the ground (instead of four).

Do you push the lever, saving the four and killing the one? Or do you not do anything and watch the train continue on its path, killing the four?

What is the most ethical choice?

In case you haven’t noticed already, there isn’t a right answer. This is a thought experiment in ethics, a branch of philosophy, and this problem has been around since the early 20th century, where it was first part of a moral questionnaire given to undergraduates at the University of Wisconsin in 1905.

To talk about this problem a bit more deeply, and to also be able to discuss some extremely interesting variants of this problem, we need to delve into and explore theories of morality.

There happen to be two primary philosophical theories that each suggest unique ways of approaching this problem. Let’s briefly examine each below.

Utilitarianism

Quite simply put, the belief that the best action is the one that maximizes “utility”. Utility doesn’t have a strict definition, but Jeremy Bentham (the founder of utilitarianism) described it as maximizing pleasure over pain. By this, he meant “…the greatest happiness of the greatest number is the measure of right and wrong.” In this case, the utility gained from saving four workers is greater than the utility gained from saving the one worker, and hence a utilitarian would push the lever.

Jeremy Bentham, 1748-1832

It’s crucial to understand that within this theory, the moral outcome of an action rests entirely on the results of the action, rather than any type of intent behind the action.

There happen to be many different versions of utilitarianism, which is part of the reason why determining whether it’s the “correct” moral theory is so difficult. The biggest dividing line between utilitarians occurs when discussing act utilitarianism versus rule utilitarianism – it’s worth quickly looking at each:

Act Utilitarianism

This is the belief that when deciding what to do, we should only have to answer one question: “Does this particular action maximize happiness?” – it is a case by case basis of dealing with situations. This is seen as often the most natural way of understanding utilitarianism, because you would think that distinct actions with nuanced consequences would require specific “calculations” each time, rather than a one size fits all method.

Example: Imagine we ask someone the question “Should you skip class next morning?” An Act Utilitarian would want to inspect the utility you’d gain from sleeping in (perhaps you have an exam later in the day and want to save sleep to do well on it) and weigh it in comparison to going to class, where even though you’re present, because you stayed super late last night studying, you won’t be able to concentrate. Perhaps, then, under such circumstances, an act utilitarian would indeed advise you to skip class.

How would they approach the trolley problem?

Saving 4 and killing 1 provides greater utility than the other way around, and so they’d push the lever.

Rule Utilitarianism

A rule utilitarian is one who asks fundamentally two questions: 1) “What is the general rule at large in this scenario?” and 2) “Would the evaluation of the rule maximize utility?” You see, a rule utilitarian doesn’t care about the specifics of a situation – when posed with the same question of skipping lecture above, he would claim that all he examined was the rule: “I should skip lecture.” Would following this rule maximize utility? No, it most certainly would not. If people stopped going to lecture, they would fall behind on material, professors’ jobs would become unclear, and students would only be paying to learn from textbooks.

Indeed, skipping lecture would most certainly not maximize happiness. The specific situation in this case doesn’t matter – the argument that skipping this lecture might allow you to do better on your exam is mute. You only abide by the general rule that states such is wrong, and that is enough to convince you to go to lecture.

How would they approach the trolley problem?

It would all depend on the overarching “rule” – is it okay to sacrifice someone for reasons that they do not share? If the answer to that is negative, then a rule utilitarian would not push the lever.

Kantianism

The fundamental opposing theory to Utilitarianism. This is Founder and CEO of said theory, Immanuel Kant, OG philosopher circa ~ 1700s.

I would like to make a pun about philosophy, but I Kant.

Kantian ethics do not revolve around the outcomes of an action. They revolve entirely around duty. They are focused on the “good-will”, choosing to do the right thing for the sake of doing the right thing. Kant states that money, courage, good looks, and power can all be used for both the good and the bad, but the good-will is something that can only be used for good.

Example: Imagine you’re a cashier and you have to return 20c in change to an old lady. You could decide to keep the 20c, but you realize that if she finds out you kept money from her, you’ll likely be perceived as a terrible human being and maybe even fired. So you do return the 20c. Now, Kant would view this as not a good action, because it wasn’t motivated by the good-will. It was motivated by a fear of getting caught. The end result may be the same (the end “utility”) but the intent different.

The only good actions are the ones that you do out of respect for the moral rules, then says Kant.

What are these moral rules?

Well, Kant believed that there was a supreme principle of morality, and he referred to it as The Categorical Imperative. This is quite simply, as phrased in this video here, the “thing” that you must do all the time, regardless of circumstances.

The Categorical Imperative

Kant explained this imperative through three different formulations; here’s the first one:

I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law.

Kant is not saying that you should only act in a way if it would be okay for everyone else to act like that.

What he is saying is that you should only act if it makes sense for you to will for everyone to act in the same way.

His second formulation of the categorical imperative:

Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or the person of another, always as an end, and never simply as a means.

Here, Kant implies that we must treat each other as objects of moral worth, not just as tools of progress for our alterior motives. You shouldn’t lie to your sister that there are no more cookies left in the jar so that you can get more of them.

This, of course, raises some interesting points about we conduct ourselves in our everyday behaviours. I mean, why do I make chit chat with my barber? Am I not treating him as a means, rather than an end? I’m only talking to him because I want my hair cut. This is true, but it doesn’t violate Kant’s statement because the barber produces his service voluntarily (in exchange for my money), and it’s not like I’m enslaving him by treating him as an ends.

Kant’s final formulation:

Act as though through your maxims you could become a legislator of universal laws.

Here, Kant wants us to remember that we are first and foremost setting an example for other people through our actions. What we as individuals do directly contributes to normal human behaviour.

Trolley Problem Under Kantianism

Now that we’ve been roughly introduced to Kant’s moral philosophy, we can examine what a Kantist would do when faced with the trolley problem.

A utilitarian (without delving into the specifics of act vs total) as we concluded above would pull the lever because saving four lives creates more utility than only saving one. A Kantist, however, does not value consequences and the argument that four is greater than one would not hold.

The simple answer is that Kantianism does not allow for the pushing of the lever; you shouldn’t kill one to save five. This is because the decision to kill another rational being is always immoral in the eyes of Kantian ethicist. You’re utilizing the lone worker’s life as a means to an end, violating his autonomy as an individual. This is unacceptable.

Utilitarianism vs Kantianism

Do you know how exciting this is?

Quite literally, we’re about to enter the battle between who possesses the bigger intellectual dick in the history of Ethics.

Note: This doesn’t have much to do with the trolley problem directly, but it’s worth understanding and elaborating at least a bit on the distinctions between these theories.

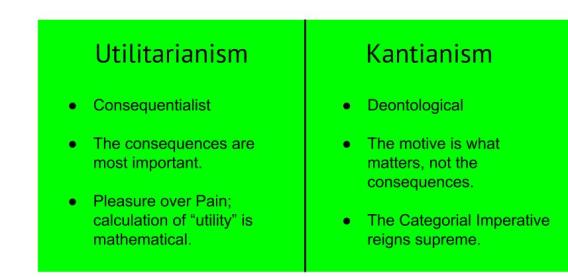

The diagram below notes the main differences:

The best way, though, to understand this is through another example.

Lying to a Nazi Soldier

Suppose you’re hiding a Jewish family in your house and you hear a knock on your door.

It’s a Nazi soldier, and he asks whether you are hiding any Jews. What do you say?

Under Bentham’s Utilitarianism, this would simply be a question of finding out which action provides the greater utility. The consequences of telling the lie are much better than the consequences of not telling the lie (since if you don’t lie, the family dies).

Hence, a utilitarian would lie.

A Kantist, on the other hand, would choose differently. According to Kant, telling a lie is always wrong, and therefore one ought to tell the truth even in this case.

But let’s step off the detached, informative lens this post has been taking; isn’t this complete madness?

Doesn’t it make complete and utter sense to lie to the Nazi Solider? After all, isn’t that overall the “good” thing to do? To prevent the likely killing of more people?

That’s what I thought the first time I was reading about Kantian Ethics, and this objection that came to mind (and that might be coming to yours) is in fact due to the theory’s lack of contextual awareness.

Whilst Kantianism is a theory of principles, it does not adequately account for the particular contexts in which we act. It can’t account for the fact that the man who knocks on your door is a Nazi Soldier or a Priest or your Mother.

Does this mean that Utilitarianism is the “superior” ethical theory?

No.

It has its fair share of problems, too. Quite fundamentally, for one, how is it possible to anticipate all possible consequences of an action? How can you know even attempt to quantify measures of pain and pleasure, when by their very nature they are varying and subjective?

And frankly, who are you to decide what is pain and what is pleasure for someone?

Similarly, think of an autonomous, self-driving car:

A fully autonomous, self-driving Car

What does the car do when faced with an emergency situation, similar to the trolley problem?

In this case, pushing or not pushing the lever would be the split second decision the car must make itself, the lone worker would be the man sitting in the driving seat of the car, and the four workers might be kids playing with a ball on the road.

Would the car have an operating system based on Kantian or Utilitarian Principles?

I’ll let you decide on that one 😉

Throwing the Fat Man off the Bridge

I promise it’s not as bad as it sounds.

This is the most popular variation to the trolley problem, and it’s set up like this:

You see a train rollicking through, about to run over five workers tied to the ground. You’re standing on a bridge, you notice a relatively large man next to you, and if you throw that large man from the bridge just before the train runs over the workers, you will kill the large man and save the five workers.

Do you push the fat man off the bridge?

Interestingly enough, though most people agree to the pushing of the lever in the original version, very few approve of pushing the fat man off the bridge.

The numerical loss of life is the exact same in both cases, and a strict utilitarian (careful, we’ll delve into specifics down below) would view both cases with equal regard. And yet, doesn’t physically assaulting that man feel more “wrong”? It goes against all our instincts and is seemingly so much more painful than pushing a lever.

Shelly Kagan, an American philosopher, initially suggests that the one clear distinction between the trolley & the bridge versions of the problem is that of intentional harm. When one pushes the lever, one doesn’t intentionally harm anyone; it can almost be said that the death of the lone worker is a “side-effect” to changing the direction of the trolley. However, in the second case, the integrality of harming the fat man cannot be disputed; come on dude, you’re pushing him off a bridge!

Now, remember how we distinguished between Act Utilitarians and Rule Utilitarians earlier? To remind you briefly:

Well, turns out that one of these kinds of utilitarians doesn’t necessarily have the same answer to both variations of the trolley problem.

It comes back down to whether one believes in the concept of intentional harm vs side effect-“uall” harm. This is essentially an application of the doctrine of double effect.

Act Utilitarians reject this claim; if the end consequences are the same (which they are), intent makes no difference.

Rule Utilitarians, on the other hand, can make the argument that there exists an overarching rule that is broken when you push the fat man off the bridge (the rule can be anything) that is necessary to maintain to maximize pleasure over pain.

Okay, let’s make this a tiny bit more interesting:

What if the fat man is the “villain” behind the planned killing of the five people? What if he has a grin on his face whilst he watches the events below him unfolding?

……..

Aaand all of a sudden, it seems almost morally imperative to push the fat “villain” man off the bridge!

I mean, that feels like the completely natural thing to do.

And yet, the fact that we now know he’s a villain doesn’t change anything.

A Kantian would still not push the man, regardless of whether he’s a villain or Mother Theresa.

An Utilitarian would still push the man, but not because he’s a villain, rather because of the maximization of utility.

This should go to show you just how hard it is to actually come up with theories of morality pertaining to all kinds of different situations. No matter what theory you believe in, there’s bound to be a situation where you’re going to feel like you’re in the wrong.

Bringing it all Together

There are just so many variations of the trolley problem, it’s pretty insane. Provided you’re still interested (ha!), you can check out a pretty comprehensive list on Wikipedia.

Hopefully, you’ve realized by now that these theories of morality we’ve examined all have their flaws. There isn’t a perfect solution to any problem, and the best we can do as philosophers is critically evaluate our ideas.

Similarly, it’s not likely that you’re ever going to face any of the situations we’ve described. Debating over hypothetical scenarios is all fun and games until you’re actually by some twisted misfortune present on that railway track, having to decide between pushing the lever or not.

I highly doubt you’re going to remember the moral theory you stand with.

So, why do we do it?

I think it’s because the discussion and argumentation that these scenarios bring forth are an extremely valuable skill to have in life.

You deal with uncertainty, attempt to bring as much logical reasoning as you can to the table, and most importantly, you listen to viewpoints that aren’t similar to yours. Not to mention the critical reading and writing required to be able to effectively argue your own viewpoint.

Further, as I briefly mentioned in one of the earlier sections, as AI becomes an increasingly bigger part of our world, such ethical dilemmas will only become more essential to discuss. Both because of actual chance of happening and for the necessary need there will be of critical thinkers who are able to “decomplicate” complicated decisions.

Note: Yes, I am trying to justify to myself that the time and research I put into this post will serve me grandly in life later.

Alright, I think I should stop rambling now. If you have any further questions I’d love to hear from you.

If you enjoyed reading this article, I think you’ll also really like this one, to do with the philosophy behind teaching English over Art.